Studio Alchimia: The Disruptive Force Behind Postmodern Italian Design

Studio Alchimia, founded in Milan in 1976, revolutionized Italian design by rejecting functionalism and mass production, instead embracing playful, radical, and interdisciplinary approaches that redefined the boundaries of design and inspired future movements like Memphis

Founded in 1976 by siblings Alessandro and Adriana Guerriero in Milan, Studio Alchimia emerged as a radical counterpoint to the rigid functionalism dominating mid-20th-century design. Rejecting the industrial era’s obsession with mass production and minimalist aesthetics, the collective became a catalyst for postmodern experimentation, blending irony, ornamentation, and a subversive reinterpretation of design history. Their work not only challenged prevailing norms but also laid the groundwork for movements like Memphis, reshaping the trajectory of Italian design.

Breaking the Mold of Modernism

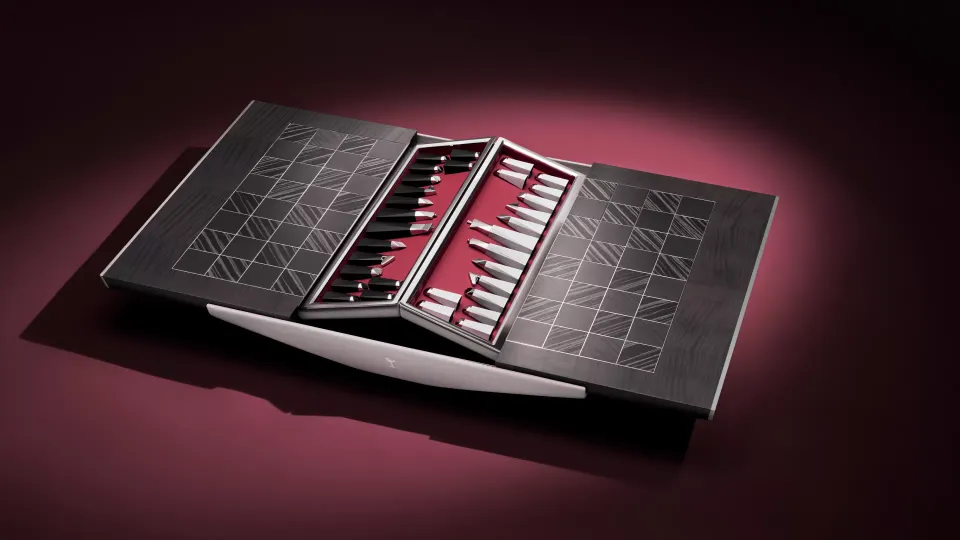

Studio Alchimia’s philosophy centered on “anti-design,” a deliberate departure from the cold rationality of Bauhaus-inspired modernism. Unlike their predecessors, who prioritized utility and industrial efficiency, Alchimia embraced chaos, humor, and cultural references. Their 1978 Bau.Haus Uno exhibition epitomized this rebellion. By draping iconic Bauhaus furniture in garish plastics or adorning Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair with decorative motifs, they mocked the sanctity of “good design” while questioning its political and social implications. This irreverence extended to materials: cheap laminates, plywood, and synthetic fabrics replaced traditional luxury finishes, democratizing design and critiquing consumer culture.

The Alchemy of Collaboration

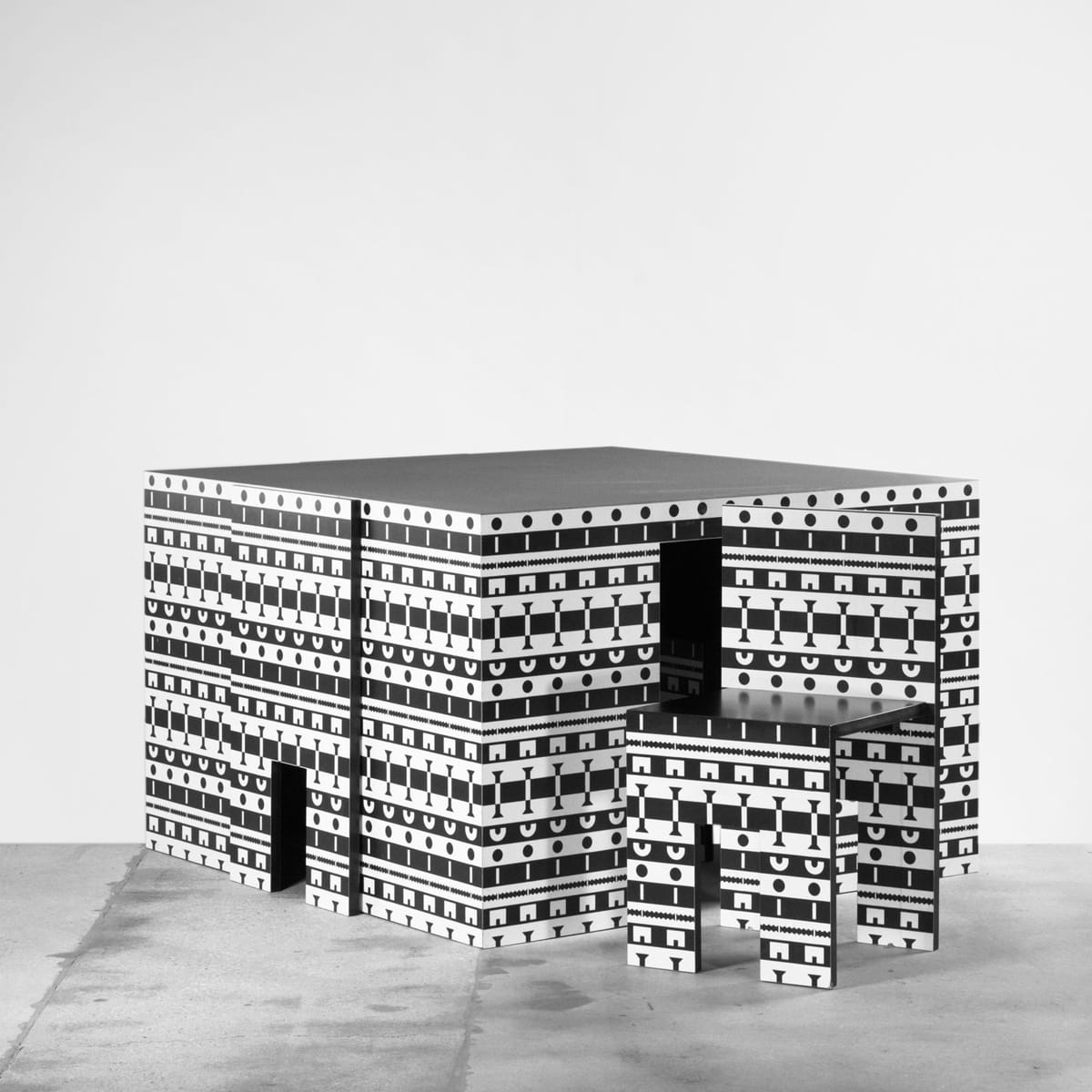

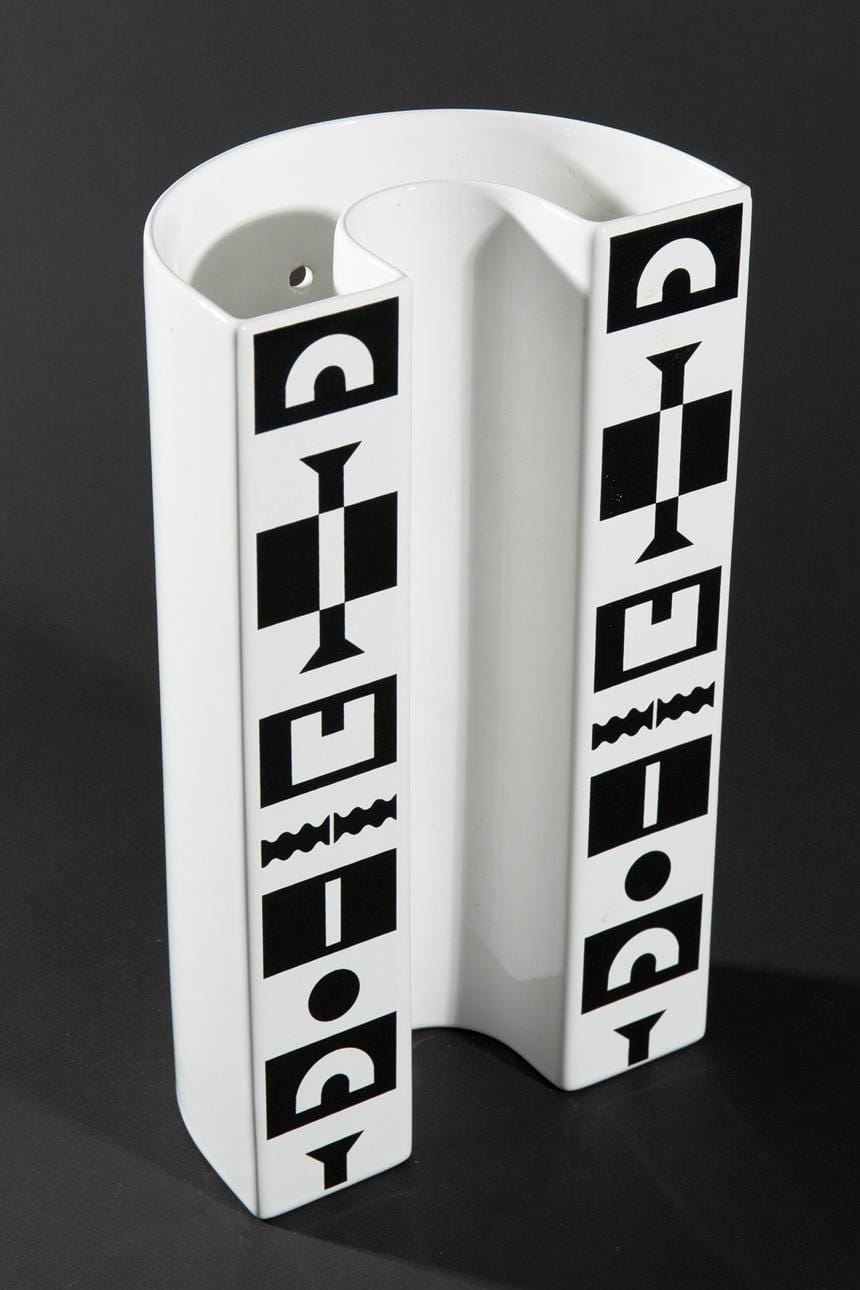

The studio thrived as a multidisciplinary collective, uniting architects, designers, and theorists like Alessandro Mendini, Ettore Sottsass, and Andrea Branzi. Mendini’s Proust Armchair (1978) became emblematic of their approach—a baroque-inspired piece upholstered in pointillist fabric, transforming a historical artifact into a postmodern icon. Similarly, Sottsass’s Kandissi sofa reimagined traditional forms with bright colors and fragmented geometries, rejecting functionalist purity in favor of emotional resonance. These works were not mere objects but “ideological carriers,” challenging the notion that design must serve industry or adhere to modernist dogma.

From Radicalism to Legacy

Alchimia’s disruptive ethos inevitably led to internal tensions. Sottsass, seeking a more commercially viable path, left in 1981 to found Memphis, which borrowed Alchimia’s playful aesthetics but embraced mass production. Despite this split, Alchimia’s influence endured. Their 1980 Venice Biennale showcase and 1981 Compasso d’Oro award for design research cemented their status as pioneers of postmodernism. Later retrospectives, such as the 2025 Bröhan Museum exhibition, highlight their role in redefining design as a medium for cultural critique, blending art, theater, and even video experimentation into their practice.

Redefining Design’s Purpose

Studio Alchimia’s legacy lies in their refusal to accept design as a servant to industry. By prioritizing conceptual depth over functionality and embracing the “banal,” they expanded the boundaries of what design could express—whether through a gaudy reimagined Bauhaus chair or a sofa designed purely as a sculptural statement. Their work remains a touchstone for contemporary designers grappling with the tension between art and utility, proving that disruption, not compliance, fuels innovation. As museums and galleries continue to revisit their oeuvre, Alchimia’s alchemical blend of provocation and poetry remains as vital today as it was in the 1970s.